(Dynamical Astronomy, Astrodynamics, and Applied Mathematics)

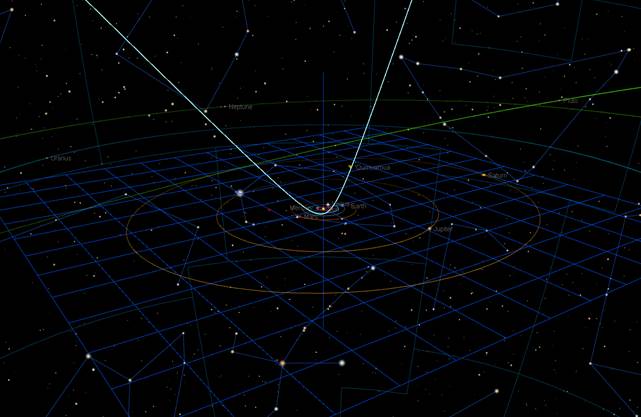

Hyperbolic path of the first-known interstellar asteroid, `Oumuamua (1I/2017 U1). Image generated using the Solar System Tools in Software Bisque's TheSky planetarium and robotic camera/telescope control program.

The discovery observations of the first-known interstellar asteroid, 'Oumuamua, were transmitted to the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center (MPC) on 2017 October 18 by the Pan-STARRS 1 observatory, located on Mt. Haleakala, Maui, Hawaii USA.

These observations were disseminated to the astronomical community via the MPC's Minor Planet Electronic Circular M.P.E.C. 2017-U183, issued 2017 Oct. 25 at 22:22 UT. In addition to Pan-STARRS 1, nine other observatories contributed to the first observational dataset, which consisted of 41 observations.

By feeding these observations into my heliocentric intial orbit determination (IOD) and differential correction (DC) programs, I was able to determine the hyperbolic trajectory of 'Oumuamua, with epoch at the time of the first observation (2017 October 18). My state vector solution is a "universal variables" two-body solution.

To illustrate the solution, I constructed the figure above using Software Bisque's TheSky planetarium and robotic camera/telescope control program (see https://bisque.com). The figure depicts 'Oumuamua on its hyperbolic path into and out of our solar system on the date 2017 June 9.

The figure shows the ecliptic plane as a mesh, and the orbits of the eight major planets, plus Pluto, situated above, in, and below the ecliptic plane. Also shown are the constellations that can be seen from this particular view in TheSky. (The ready availability of these planetary and stellar depictions via TheSky's Solar System Tool is why I chose to use TheSky to illustrate the path of 'Oumuamua.)

Here are the source code, an input file, and an output file for a C++ Builder 5 program, htm1.cpp, that I wrote to model the trajectories of heliocentric objects using universal variables. The input and output files are for 'Oumuamua's path from 760 days before epoch to 730 days after epoch.

Source file: htm1.cpp Input file: htm_inp.txt Output file: htm_out.txt

Other than having initial double forward slashes (//) preceding some of the comment lines near the beginning of the program, I do believe that the source code is ANSI Standard C.

Now Stumpff's c-functions, as defined and invoked in htm1, and as further documented in my MAA-RMS presentation provided below, may be of interest in themselves. So here is a C program that calculates the first six c-functions of an input argument x. It reads input arguments from the console (the "Command Prompt" window) and writes output to the text file cf5_out.txt.

Source file: cf5.c

Translation of the above source codes into one of the more contemporary (but typically non-compilable) computer languages such as Python, Java, or MATLAB is encouraged.

I share these C/C++ source codes to commemorate and apply the work of the German theorist Karl J. Stumpff, who in 1947 saw his seminal article "Neue Formeln und Hilfstafeln zur Ephemeridenrechnung" (*) published in the German journal Astronomische Nachrichten (Astronomcal Reports).

(*New Formulas and Auxiliary Tables for the Calculation of Ephemerides)

My own work in universal-variables-based orbit propagation traces back to this article. WILEY-VCH Verlag Berlin GmbH holds the copyright. But the article, in German, is readily available from the NASA Astrophysics Data System.

This concludes my webpage topic "Modeling the Hyperbolic Trajectory of the First-Known Interstellar Asteroid, 'Oumuamua". Please click on the link below to go back to the top of this webpage.

I have been invited to speak at the 2019 meeting of the Rocky Mountain Section (RMS) of the Mathematical Association of America (MAA), to be held April 5-6 at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado USA.

The topic of my presentation is "WHAT ARE UNIVERSAL VARIABLES? How Do They Describe the Path of the First-Known Interstellar Asteroid, 'Oumuamua?"

Click on the link below to see the slides for my presentation:

MAA-RMS_Presentation_Durango_2019_April_6_v.3_Dell_7530.pdf

This concludes my webpage sub-topic, "Related Presentation for MAA Rocky Mountain Section Meeting". Please click on the link below to go back to the top of this webpage.

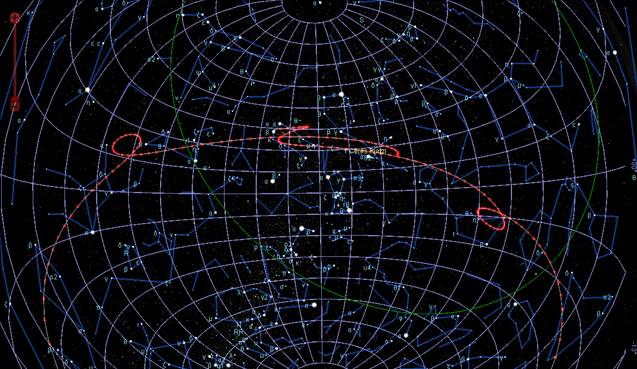

Path of Ceres from 1801 January 1 to 1806 May 23. This figure shows what the path of Ceres, as a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt, looked like from the date of Ceresís discovery by Piazzi through its observation by Olbers, Harding, and Bessel in 1805-1806.

"Reconstruction of the 1801 Discovery Orbit of Ceres via Contemporary Angles-Only Algorithms" is the title of a paper that fellow astrodynamicist Dr. Gim J. Der (see Der Astrodynamics) and I prepared for presentation at the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies (AMOS) Conference 2016, held in Maui, Hawaii USA, during September 20-23, 2016. To download our paper from the AMOS website, click on

amostech.com/TechnicalPapers/2016/Poster/Mansfield.pdf.

The figure above is excerpted from a 48-inch wide by 36-inch high poster that accompanies our paper. The poster can be viewed by clicking here: ceres_1801_poster.

For this analysis we input the 19 complete discovery observations of the first known asteroid, Ceres, to our contemporary initial orbit determination (IOD) and differential correction (DC) computer algorithms in order to solve for the heliocentric ecliptic state vector and osculating orbital elements of Ceres that describe the motion of the dwarf planet in 1801.

A very brief history of the discovery and recovery of Ceres now follows, together with further information relevant to our own analyses and results with the discovery observations.

Giuseppe Piazzi discovered Ceres on 1801 January 1 and observed it almost nightly until February 11. Baron Franz Xaver von Zach, editor and publisher of the German-language astronomical journal Monatliche Correspondenz ("Monthly Correspondence", abbreviated below as "MC") published Piazzi's observations in the 1801 September issue of MC on p. 280.

The astronomers Carl Friedrich Gauss, Wilhelm Olbers, Johann Burckhardt, and Piazzi each determined orbital elements and search ephemerides for Ceres as the result of independent calculations that started with Piazzi's discovery observations. Their results were discussed by von Zach in the October, November, and December issues of MC. Also discussed were the cloudy, overcast conditions in Europe during much of the year 1801, and the frustration of the European astronomers in not being able to recover and observe Ceres and update its orbital elements.

Then, finally, on the night of 1801 December 31 - 1802 January 1, von Zach recovered Ceres using only Gauss's search ephemeris. Gauss subsequently became famous as an astronomer as the result of the orbit determination procedure that he conceived and applied in order to determine the orbital elements of Ceres and compute a search ephemeris.

Gauss eventually became regarded, then as now, as one of three greatest mathematicians who have ever lived -- these three greatest mathematicians being, according to Eric Temple Bell (himself an eminent 20th century mathematician): Archimedes, Gauss, and Newton. (See Bell's Men of Mathematics, Chapter 14, for Bell's biography and assessment of Gauss.)

Gim and I originally thought that we would simply vet the 19 complete discovery observations of Ceres using modern computers and our contemporary angles-only algorithms. But in the course of our research we found that von Zach's MC, written in German, had recently become available as a Nabu Public Domain reprint. So we obtained the MC reprint and translated into English the key article from 1801 December, the one with Gauss's search ephemeris on p. 647. That key article, in German, and a page-by-page summary of the facts relevant to our contemporary research, can be viewed from the two links immediately below:

von Zach's Monatliche Correspondenz, Vol. 4 (1801 December), pp. 638-649

Summary of von Zach's MC, Vol. 4 (1801 December), pp. 638-649.

Given Gauss's published search ephemeris, and the obliquities of the ecliptic that we now computed for the dates of the observations, we were able to convert the geocentric ecliptic longitudes and latitudes in the search ephemeris to right ascensions and declinations using the appropriate equations from spherical trigonometry. Now we were able to compare our contemporary solutions' predicted ephemerides directly with Gauss's own search ephemeris.

There was an unexpected finding. For more about this, download the paginated, pre-publication draft of our paper at

mansfield_der_amos_2016_09_15_preprint.pdf

and see the ADDENDUM, pp. 17-19.

Reference 13 of our AMOS 2016 paper cites two Mathcad 15 worksheets viewable here. The two worksheets, in .pdf format, are:

These two worksheets completely specify our Batch UPM DC algorithm as applied to the 17 best observations of Piazzi during 1801 January 1 - February 11.

I have been invited to speak about my AMOS 2016 poster and paper at the DAS general meeting at 7:30 p.m. on Friday evening, April 7, 2017 at the University of Denver's Olin Hall, Room 105. Click on the link below to see my PowerPoint presentation:

DAS 2017_04_07 Presentation.pdf.

This concludes the information about my presentation to the Denver Astronomical Society.

I have been invited to speak at the 2018 meeting of the Rocky Mountain Section (RMS) of the Mathematical Association of America (MAA), to be held April 13-14 at the University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colorado.

The topic of my presentation is "MODERN SPACE SITUATIONAL AWARENESS -- It Began with Piazzi, von Zach, and Gauss in 1801." This presentation was suggested by paragraph 7 of my AMOS 2016 paper, "7. SPACE SITUATIONAL AWARENESS: THEN AND NOW." Click on the link below to see my PowerPoint presentation:

MAA/RMS Presentation Greeley April 2018.pdf.

On p. 17 of this presentation I refer to a Mathcad worksheet that I constructed to show how to convert the geocentric ecliptic longitudes and latitudes in Gauss's search ephemeris into right ascensions and declinations for plotting on a star chart. Click on the link below to see that worksheet:

Ceres_Search_Ephemeris_by_Gauss_1801_December.pdf.

The star charts on pages 3, 19, and 20 of my presentation did not take well to being pasted into PowerPoint as .jpg images, followed by conversion to .pdf, even with high-quality print selected as a conversion setting. Click on the link below to download the three star maps in a resolution suitable for printing on a laser printer:

SKY MAPS 2018.pdf.

In the "Tools" menu of Adobe Reader, be sure to specify Rotate > Counterclockwise to view the star maps in their intended landscape orientation.

Map 1 is a rectangular projection of the entire celestial sphere onto a plane. The stars are grouped into constellations by pattern lines. Pattern lines facilitate memorization of the appearance of the night sky, while the constellations themselves provide a framework for locating the brighter planets, stars, and other celestial objects.

Map 1 is "unbiased" because it is never completely upside down. For if north is up and you rotate the map 180 degrees, south is now up and you can still read the map's upper celestial hemisphere labels right-side up (try it).

Note the right ascension (RA) scales on the upper and lower borders of Map 1. These allow you to determine the local apparent sidereal time at your longitude by the following two rules.

To find the RA of the stars crossing your celestial meridian at midnight on a given date, use the dates and the RA scale for your geographical hemisphere (northern or southern based upon your latitude) as a guide to estimating the placement of a line perpendicular to the RA scales and passing through the given date on both RA scales. This perpendicular line is your celestial meridian line at midnight. Note that each "tick" on the RA scale corresponds to about four calendar days as well as to exactly 15 minutes of RA.

To locate the celestial meridian at a given hour on the date used for Rule 1, move the celestial meridian line west (decreasing RA) one hour of RA for each hour earlier than midnight. Move the celestial meridian line east (increasing RA) one hour of RA for each hour later than midnight.

Since the celestial meridian is the extension of the great circle of your geographical longitude onto the celestial sphere, it marks the local apparent sidereal time. Its location in the sky at any point in time tells you what stars and constellations you can see as you look south (northern hemisphere observer) or north (southern hemisphere observer) along the celestial meridian.

Map 2 is a polar equidistant projection of the north celestial hemisphere onto a plane, plus another 45 degrees of southern declination. It is therefore good for northern hemisphere observers.

Map 3 is a polar equidistant projection of the south celestial hemisphere onto a plane, plus another 45 degrees of northern declination. It is therefore good for southern hemisphere observers.

The 57 celestial navigation stars are labeled on all three maps, where visible, plus other bright stars as indicated on the maps.

Dr. Barbara D. Buchalter (1929 April 13 - 2005 November 26)

Professor of Mathematics, University of Nebraska at Omaha

"Dr. Buchalter taught me Complex Variables and Conformal Mapping"

This concludes the information about my presentation to the Rocky Mountain Section of the MAA.

This concludes my webpage topic "Reconstruction of the 1801 Discovery Orbit of Ceres." Please click on the link below to go back to the top of this webpage.

"Nonlinear Dynamics Using Mathcad Prime 1.0"

was the title of a presentation that I recorded at PTC World Headquarters in Needham, Massachusetts on March 15, 2011 -- for viewing at the PlanetPTC Virtual Mathcad Event held on April 14, 2011.

My goal in the presentation was to show that, while Mathcad Prime 1.0 was not yet ready to take over the role of Mathcad 15, one could nevertheless use it right then to do some rather sophisticated nonlinear dynamical modeling.

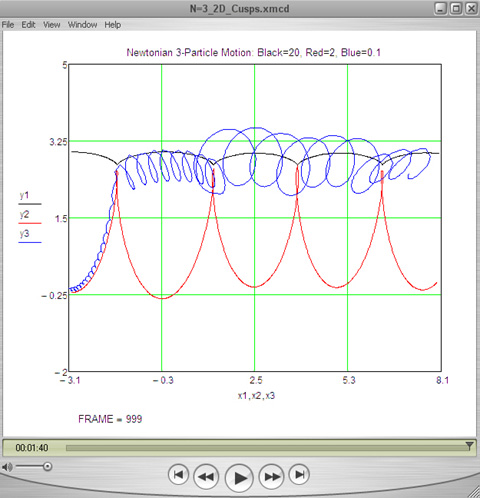

To see what I meant, consider the figure above. It looks like black, red, and blue scribbles as might have been made by a child using colored pens or crayons.

But in fact the figure is the result of integrating numerically the trajectories of three massive particles obeying the three highly-nonlinear, second-order, ordinary differential equations embodied in Newton's universal law of gravitation.

For an animation of the figure, click on Colliding_Planets.pptx and open with Microsoft's PowerPoint program. (For the associated files in Mathcad worksheet or PDF format, ask.)

PlanetPTC was the union of new online PTC communities that included users of the CAD programs Creo Elements/Pro (formerly Pro/ENGINEER) and Mathcad, as developed by Parametric Technology Corporation (PTC) of Needham, Massachusetts USA.

To see a clickable list of all of the PTC communities as they have evolved since 2011, see https://PTC.com/.

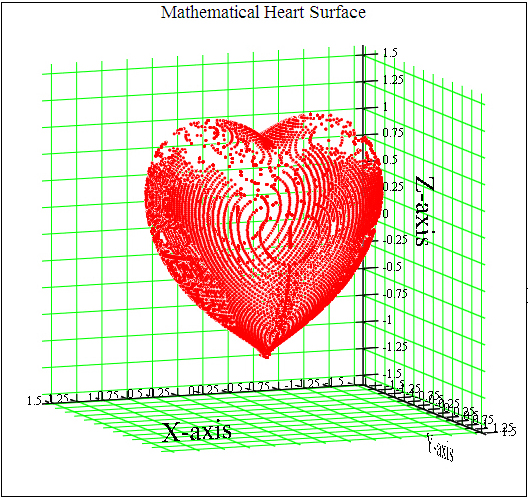

In January 2011, Dan Marotta, the PlanetPTC webmaster, challenged Mathcad users to draw a heart surface such as was shown at the German website

Mathematische Basteleien (Mathematical Tinkerings). I responded with the plot shown above. It is actually a "pointillist" plot, i.e., it is a 3D scatter plot of points lying on the surface of the heart.

The mathematical heart surface depicted above has both bilateral (side-to-side) and dorsal-ventral (back-to-front) symmetry. I needed to take advantage of these symmetries in order that my plot not take too long to calculate in Mathcad.

If you do not have Mathcad 15, you can view my worksheet as a PDF file by clicking on Mathematical_Heart.pdf.

Anatomy enthusiasts will note that the mammalian heart has neither of the two true symmetries of the mathematical heart depicted above.

This is because, although the mammalian heart has left and right atria and ventricles, suggesting at least bilateral symmetry, the "blue" (oxygen-depleted) blood returns from the body to the right atrium and is pumped to the right ventricle, and then on to the lungs, while "red" (oxygen-enriched) blood returns from the lungs to the left atrium and is pumped to the left ventricle, and then on to the body via the aortic artery.

Why do I mention the mammalian heart in this context? Because there was actually an animation of a beating mammalian heart in the Mathcad videos at PlanetPTC. I can no longer find it online; but a search for "Beating Heart" now will yield numerous hits on your favorite search engine.

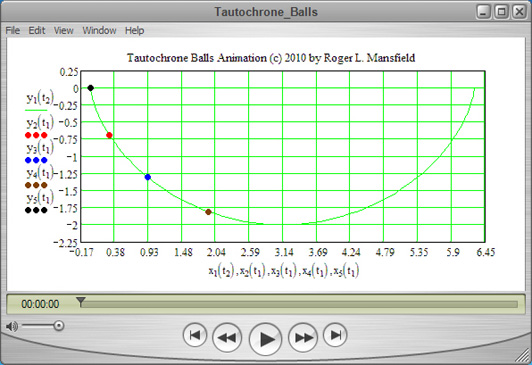

Four balls, initially at rest, are poised to slide down a curved path, as illustrated in the figure above. Assume that the balls are acted upon by the downward pull of gravity alone, with no rolling friction nor wind resistance.

Which ball will be the first to arrive at the bottom of the curve, at the point x = pi, y = -2?

For the answer, click on this link:

Tautochrone_Balls.avi. The answer may not be what you expect!

The Mathcad 15 worksheet was available for download from the August 2010 issue of PTC Express. You can now view the Tautochrone Balls worksheet as a PDF file by clicking on Tautochrone_Balls.pdf.

Mathcad Worksheets by Astroger describes fifteen Mathcad Prime 10 worksheet applications for dynamical astronomy, astrodynamics, celestial navigation, botany, and physics. All are downloadable in portable document format as .pdf files. You do not need Mathcad to read these .pdf files.

http://mathcadwork.astroger.com/.

Topics in Astrodynamics describes my astrodynamics textbook of the same name, and provides

resources toward using the book to teach a two-semester graduate course sequence, Astrodynamics I and

Astrodynamics II. Go to

http://astrotopics.astroger.com/.

Orbital Mechanics with Mathcad lists the lesson plan topics for my

course for space professionals in Colorado Springs. The course focused on the unique capabilities of Mathcad for orbital mechanics algorithm development and documentation. For further information go to

http://astrocourse.astroger.com/.

Space Ornithology is a webpage that documents my contributions to artificial Earth satellite observation as regards (a) writing and publishing the Space Birds computer program in 1987, and (b) coining the term space ornithology as the study of the space bird population (satellites in low-Earth orbit visible with the naked eye), and (c) publishing sixteen quarterly issues of the Space Ornithology Newsletter during 1988-1991. Go to

http://space-birds.astroger.com/.

In the decade after the launch of Sputnik I, the U.S. Air Force took great strides in Space Domain Awareness (SDA) under the leadership of military space pioneers such as Dr. Louis G. Walters. For some recent links mentioning Dr. Walters and the Aeronutronic Division of Ford Motor Company, see the Wikipedia entries

Project_Space_Track (1957-1961), and

1st_Aerospace_Surveillance_and_Control_Squadron. (For more about Dr. Walters, contact me.)

New career fields opened up for satellite controllers

and for orbital analysts. Professional space training for these new space career fields was set up at Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi.

I attended two courses as a part of this new "Cold War" professional space training: the

three-week Space Operations Officer Course and the eight-week Orbital Analyst Course. My

fire for orbital mechanics was kindled at the first course and intensified at the

second. In my post-service career, I actively and successfully sought opportunities to do

orbital mechanics for a living, and to teach orbital mechanics (i.e., astrodynamics) as well.

Much of the orbital mechanics that I was doing applies to natural

celestial bodies and space probes as well as to artificial Earth satellites. And so

my interests began to encompass dynamical astronomy as well as astrodynamics. These

Astroger Webpages are thus devoted to both fields.

*Astroger is the union of the letters in "Astro" and the letters of my first name, "roger". Astroger is pronounced "Astro-jer" (soft "g"). Do not confuse "astroger" with "astrologer" (Google has). I am one who calculates trajectories using the principles of dynamical astronomy (celestial mechanics). An astrologer might use my own planetary ephemerides and your birthdate to cast your horoscope. But I do not do that.

(c) 2011-2025 by Astronomical Data Service. Last updated 2025 April 04.

Trajectories of three Newtonian particles numerically integrated using Mathcad Prime 1.0.

Mathematical Heart Surface plotted via Mathcad 15 and posted to PlanetPTC.

Tautochrone Balls animation featured in PTC Express Newsletter of August 2010.

E-mail: astroger@att.net

|

Accesses:

|